Book Review | Arquine

Arquine, a major Latin American architectural publication, has published an in-depth review of our new monograph that highlights its “elegant art book format and its juicy content.” The original Spanish review can be read online, or check out the English translation here:

Published by University of Texas Press at the end of 2020, Miró Rivera Architects: Building a New Arcadia condenses, in 20 works, 20 years of work by an American firm founded by two Hispanic architects in the idiosyncratic city of Austin, Texas (the “New Arcadia” of the title). It is a great book, in both its elegant art book format and its juicy content that brings together texts by Michael Sorkin (before COVID-19 took him from us), Juan Luis de las Rivas Sanz, Juan Miró and Nina Rappaport, as well as an evocative photographic essay with two dozen works captured by Sebastian Schutyser with a pinhole (lensless) camera and a delicious interview by Carlos Jiménez with the studio partners: Juan Miró from Spain and Miguel Rivera from Puerto Rico. Both were born in the summer of 1964, three weeks and 4,000 miles apart; they met in 1991 in New York working for Gwathmey Siegel Architects; they became friends and then relatives after Juan married Miguel's sister, Rosa, a specialist in Latin American art who has played a fundamental role in the firm’s success.

Although he was born in Barcelona, Juan grew up in Madrid, where he studied while working with his father, the architect Antonio Miró, who designed some iconic works in Spain in the second half of the 20th century with his partner, Fernando Higueras. Shortly after graduating from college, Juan won a Fulbright scholarship to pursue a postgraduate degree at Yale, where he was taught by Charles Gwathmey—one of the famous “Five Architects” from New York (the quintet was completed by Peter Eisenman, Michael Graves, John Hedjuk and Richard Meier). The teacher invited the student to collaborate in his office, where Miguel already worked after graduating from the University of Puerto Rico and Columbia. Shortly after meeting, Miguel moved to another studio in the "big leagues" (Mitchell Giurgola Architects, where he became an associate) while Juan was put in charge of the residence of Michael Dell, the new owner of Dell Computer Corporation, to be built in Austin. Juan and Rosa were captivated by this “landscape city” and decided to trade the concrete jungle and skyline of the Big Apple for the soft forested horizons of the bucolic Texas capital. Juan became independent and formed his own studio with Rosa's support. They bought an old, large house that was already functioning as an office in one of the historic suburbs, and adapted it for its new use. It was not easy, but they managed to convince Miguel to leave Manhattan for Austin to partner and found Miró Rivera Architects (MRA).

“Keep Austin Weird” is the battle cry of Austinites trying to maintain the identity of their city compared to the great Texas metropolises that surround it: San Antonio, Houston and Dallas. Austin is the capital of the vast territory of Texas—the second largest state in the Union—which was New Spain until 1821 and then part of Mexico until the state achieved independence in 1836, just a decade before becoming the 28th star on the American flag. Stephen F. Austin, leader of Texas independence, was the namesake of that new “arcadia” (the mythical earthly paradise of ancient Greece) to which the title of the book refers. The city is a rare bird that clashes with the kitsch and flamboyant stereotype of Texas: cultured and sophisticated, it has grown exponentially in the 21st century and is consistently rated as one of the cities with the best standard of living in the United States. A center of technological innovation, its famous festivals—such as the Austin City Limits Music Festival—make Austin the “Live Music Capital of the World” (another of its slogans along with the famous “Keep Austin Weird”).

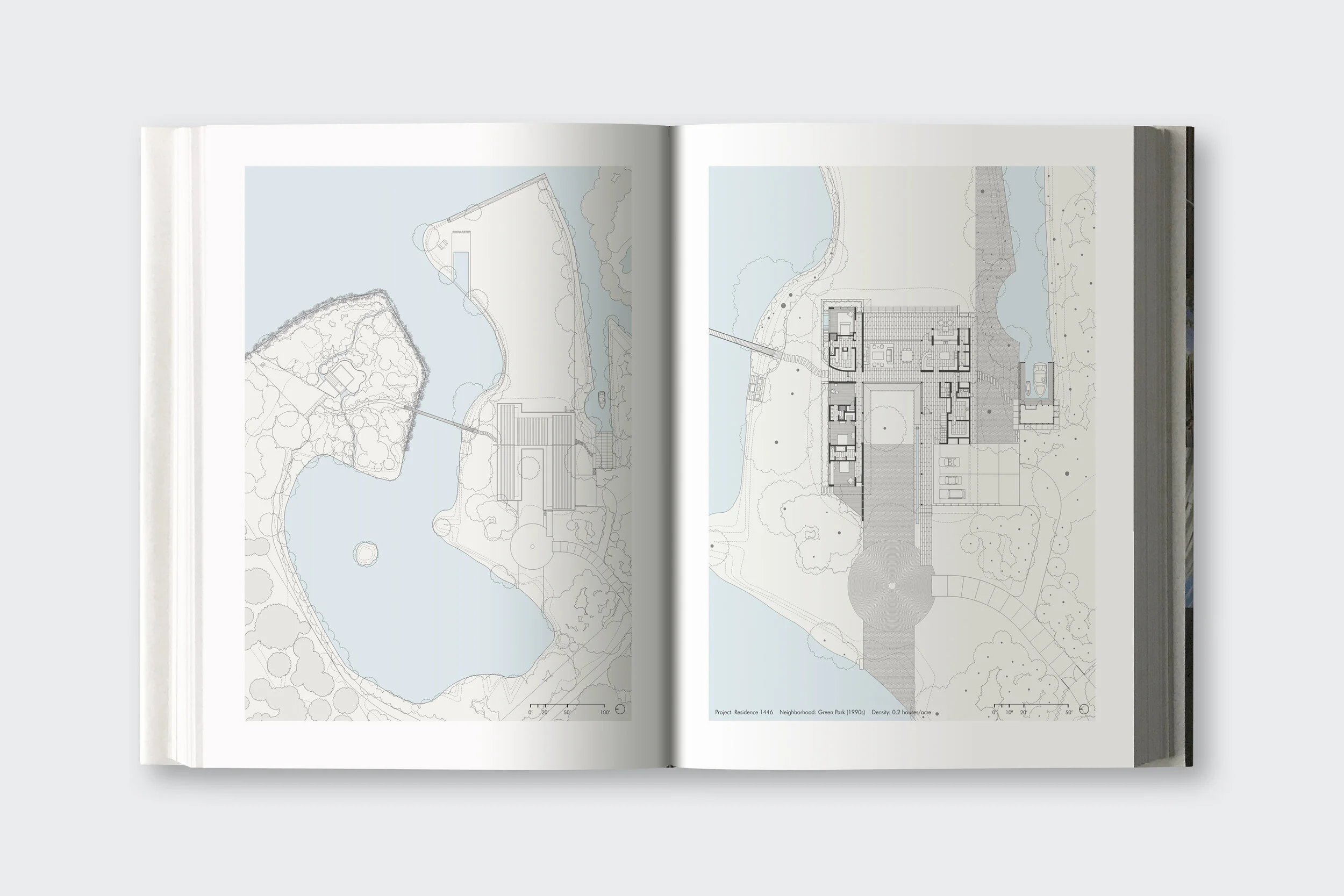

In addition, Austin is home to the flagship campus of The University of Texas, and the student population injects the city with an invaluable youthful effervescence. The university’s School of Architecture (UTSoA) is one of the “top ten” in the country, and Juan Miró has been part of its faculty for more than twenty years (before even associating with Miguel). Juan’s academic streak is felt in this publication with the essay “The Landscape City,” in which the professor explains this concept as applied to Austin and the relationship of its inhabitants with its rich natural environment (forest and river), supported by magnificent aerial views of the metropolitan area captured by photographer Iwan Baan. Juan’s analysis is completed with a kind of urban taxonomy that takes as reference ten residences designed or remodeled by MRA (including those of the two partners); each of them is presented with a photograph and two plans: a set that covers 10 acres to understand the context and density of the neighborhood in which they are inserted, and a larger-scale architectural plan to appreciate the layout of the interior and exterior spaces of the house.

The focus of the book with which MRA celebrates its first two decades of work is centered on twenty selected projects that range from a public toilet or a small pedestrian bridge to a Formula One circuit: private residences (its most frequent commissions), recreational docks (Lake Austin Boat Dock), cultural or religious centers (Performing Arts Center for Austin’s public schools, Chinmaya Mission for the Hindu community), Texas ranches (they could not be missing in the land of farmers and cowboys), and mixed-use buildings (LifeWorks for a Texas nonprofit, Citica for a Monterrey developer). They are presented without a particular order (neither chronological, nor typological, nor scalar) and with an excellent quality of graphic support: a hundred drawings (sketches, plans, axonometric construction details) reproduced at a generous scale to be able to analyze them in detail, and more than 200 full color photos. Almost all of the works are located in or around the Austin metropolitan area, except for a handful in surrounding cities (a bus stop in San Antonio, the “Vertical House” in Dallas, two residences in Houston) and two projects completed in Monterrey, on the other side of the Rio Bravo (or Rio Grande, depending on the point of view from here or there) that divides Texas and Nuevo León. These Mexican works, made in collaboration with the Monterrey office Ibarra Aragón Arquitectura, represent the beginning of the internationalization of a studio that intends to continue maintaining its domestic scale beyond borders and regardless of the size of the commissions.

Curiously, it was their smaller-scale projects that gave MRA international visibility. Both were conceived as pieces of land art: a public toilet (Trail Restroom) in the Lady Bird Lake urban park that recalls the sculptures of Richard Serra, and the pedestrian bridge that joins the main house and guest house in a property on the outskirts of Austin (Residence 1446), made with a simple metal structure and rods that recalls the reeds that abound in the wetland site. At the other end of the scale is MRA's most famous work: the spectacular Circuit of The Americas, which has hosted the United States Formula One Grand Prix since 2012. The architects’ approach was to design according to a modular system that allowed the necessary facilities (bleachers, commercial premises, bathrooms and services) to be completed in a short time. But they also took advantage of the opportunity to convert a huge open space that would have been used infrequently into a public park. This open forum holds concerts and massive events, topped by a 250-foot-tall lookout tower that allows great views of both the circuit and the surrounding landscape, and that has been become a landmark for Austin.

The publication collects reflections on the work of Miró Rivera Architects by two great figures that American architecture has lost: Charles Gwathmey (1938-2008) and Michel Sorkin (1948-2020). In his essay “Monks and Cowboys,” Sorkin argues that “whatever the intensity or complexity of the project, resources are never wasted; they are used accurately and economically (luxury also implies economy). Their forms evolve, but always within a natural range that gradually expands with new knowledge and experiences.” For his part, Gwathmey wrote years ago: “The work of Miró Rivera is poetic, thoughtful, rigorous and varied. It's not about size but about content, and it exploits the idea that constraints provide design and creation opportunities.” This book confirms both statements.